“Repeat after me, ‘I am a diabetic,’” the nurse said. “It’s part of the coping process.”

“You were a few days away from slipping into a diabetic coma...and you would not have survived past 24 hours.” My sister told me on my 23rd birthday, September 28, 2019. I was discharged from the ICU where I had spent the previous two days with diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of Type 1 Diabetes, a condition in which the pancreas stops producing insulin. The cause is unknown.

I chalked up the fatigue and 20-pound weight loss to the marathon I was training for. I attributed my dry mouth to the California heat, even though I gagged every morning when I took a drink of water. My cycle stopped for three months and I was unable to hold my bladder. I explained away each symptom until, finally, I struggled to breathe.

For the first two months before getting my durable medical equipment, I pricked my fingers about 8 times a day to check my blood sugar and gave myself about 4 insulin shots a day when eating.

I moved back into my childhood bedroom for a couple months where my only responsibility was to take care of my body.

“I just wish I could turn this off for a day. I can’t eat anything without thinking about it. I can’t workout without thinking about it. I can’t sit for too long without thinking about it. Literally every hour I expend energy thinking about blood sugar.” -journal entry December 15, 2020.

If I don’t give enough insulin to cover carbs, my blood sugar jumps high. Longterm, this leads to blindness or neuropathy, which is nerve damage that can require amputation.

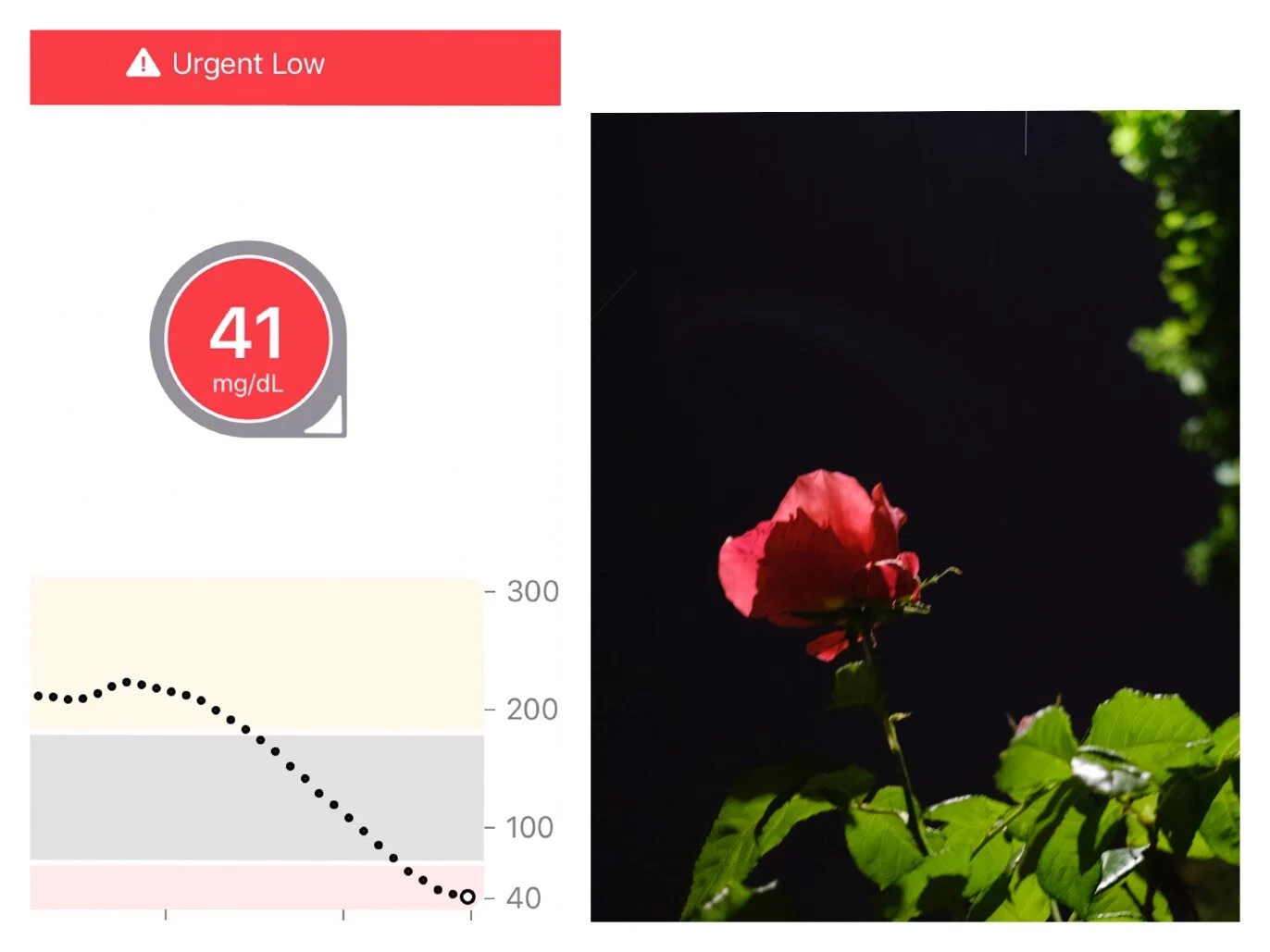

If I give too much insulin, then my blood sugar drops. I become light-headed and risk passing out, and eventually this leads to brain damage or death. But if I habitually eat carbs to correct my blood sugar even when I’m not hungry, then I risk weight gain.

The target blood sugar range is 80-130, color-coded grey.

My dad-doctor wrote this reference sheet with target blood sugar numbers and symptoms.

Dad wrote me: “I know that God doesn’t make mistakes and am confident that your life will glorify Him more as a diabetic than it would otherwise.”

Without insulin, the body feeds on fat and eventually muscle to survive, and this releases ketones, which are acids that become toxic if too many build up at once. Prior to the diagnosis, my body was burning fat to survive, which explained the extreme fatigue and weight loss. Losing fat at a rapid pace released ketones, which my body attempted to get rid of through frequent urination and deep raspy breaths.

My hair had fallen out in chunks because my body had shut down all non-essential tasks during survival mode. It took ten months to fully grow back.

Ironically, it took almost dying to feel content in my own skin. My body was leaner; my curves were gone. For the first time, I was completely satisfied with my reflection. But once I healed, my insecurities returned.

It feels like my health is constantly tested, analyzed and graded.

Carbs are the gas in the tank for our bodies. Carbs give our bodies energy while protein and fat serve other purposes. I can still eat my favorite high-carb foods as a diabetic, but I’m more intentional about when.

Sitting down for hours or going on a long run vastly alters how much insulin my body needs. A half-cup of oatmeal with banana requires seven units of insulin, or a 6-mile run, or four units of insulin followed by a 1-mile walk.

I woke up in the middle of the night with high blood sugar, so I dragged myself out of bed to do 300 squats, 30 pushups and two 2-minute planks, which brought my blood sugar down by 150 units.

A pandemic induced virtual doctor appointment with my endocrinologist and roommate’s cat, Rob. Since getting diabetes, my A1C has fluctuated between 5.6 and 6.6. (A1C measures average blood sugar from the past three months. Below 5.7 is the standard recommendation, but Type 1 Diabetics are given wiggle room up to 7.0.)

The first time I wore a bikini since getting the blood sugar monitor. (photographed with assistance from Emilie Faiella)

“Is that your pager?” … “Do you use an old-school cellphone?” People ask about this PDM, my personal diabetes manager that connects wirelessly to the insulin pump on my body. It is pictured here, cracked, after learning how to skateboard.

My goal is 100%.

I am now immunocompromised and will always have a pre-existing health condition. I accept that. Mostly, I am grateful that this condition is manageable.

If I could change something about my appearance, it would be my scars, mostly from the insulin pumps. But I also know that scars are a mark of healing, and one day I hope to see my scars as small miracles.